The flood water fell, the sky is a gray sheet, and Eric Monsi is shaking his head. More than two days after the help of a gruesome flash victim, he still does not believe his eyes.

About 90 hours ago, heavy rains sent the Guadalobi River, which rises through this picturesque sub -division. After they were trapped in their homes and their neck in the water, the residents now stand in an inch of mud while returning to their homes. Their faces are shocked and shocked, surrounded by the water waste whose property was.

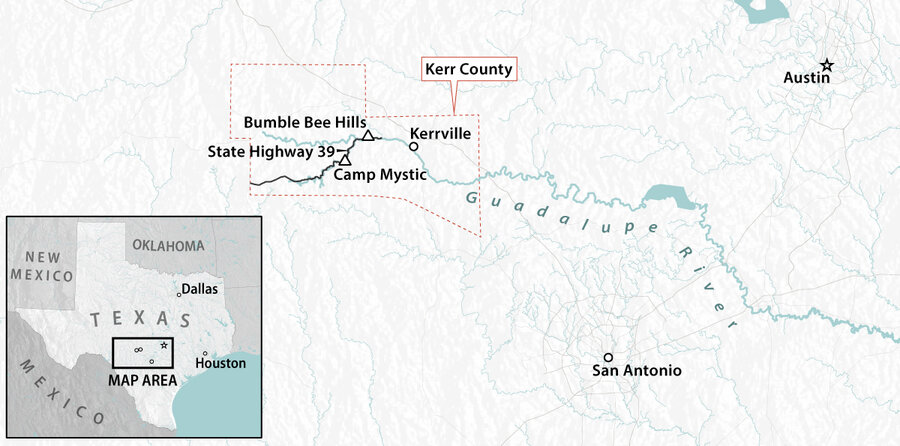

But they still have their lives, and the population hesitates in interviews. More than 100 deaths were reported in Texas after heavy rains during the fourth weekend in July, which caused a large flooding in the heart of the state. Care, a rural area of about 54,000 people, was the most difficult blow. Provincial officials announced 87 deaths, including 56 adults and 30 children. Five of the camps and one consultant in the Mystic camp – a famous girls camp on the banks of Guadalobi – remained imperceptible on Tuesday morning.

Why did we write this

After the catastrophic floods in the center of Texas, the residents turn each other for support. Efforts include launching donation engines and bringing supplies to hard -to -reach neighbors.

Mr. Monsey, the Beck August truck is driven full of cleaning supplies and electrletic drinks, in bush from the hills of water property.

He says, “This is the lives of the entire people,” and he rests a hand of tattoo on the wheel. “People literally throw their homes completely.”

But he adds, “All this is Texas.”

He talks about people now, not property. He talks about the two friends who help him to deliver supplies to the victims of the flood, and about friends and relatives who help in the gut, and the respondents in emergency situations who are still intersecting through miles of clay, debris, and flat cypress trees when they enter the fifth day of efforts to search and balance.

The days were unclear together as the inhabitants of this picturesque pocket – escaping to nature for generations of Texas – continued treatment and recovery from one of the bloodiest natural disasters in the history of the state. The local population has reached their faith and society – donating food, clothes and time for those who lost more than they did – and took a painful rush of donations from all over the country and the world.

Christina Hernandez has been on average of four hours of sleeping night since Independence Day. She is a waiter at Wilson’s Ice House in Kerrville, and it helps in converting the cohesive bars and restaurants network in the region into improvised donation centers.

On Monday afternoon, it helps in organizing clothes and food in the Fritzer salon in Ingram. The night before, it was cooking free meals for the first respondents. A mixture of upper helicopter, police and warning fire, and adrenaline kept their work for 20 hours after 20 hours a day.

The donations were so huge that its team began to convert its focus to beyond the most difficult areas along Guadalobi. Mrs. Hernandez helps take clothes and supplies to neighboring cities. Half of the people who stopped supplies survived severe flood damage, but they lost their critical salaries because their workplaces were washed, or they are struggling in the wake of slight damage to the floods.

“We have to think about the only parents, the families of one financing, and the people whose ages range from salaries,” she says.

Diapers and donation systems

Mrs. Hernandez sits on a shaded outdoor table, and recounts the donations that have accumulated in Fritzer, by the local population: clothes, especially for the elderly; Cleanliness groups water wipes; diapers.

Courtney Johnson, sitting at a close table, holding.

“Have you really got diapers?” You ask. She adds that she has three children, and she is trying to train Al -Qamar. The withdrawals will be perfect.

“I think I have some in my car,” Mrs. Hernandez answered.

“I have been given clothes,” says Ms. Johnson.

She says that the group of volunteers for Mrs. Hernandez has supplies for anyone who needs help. The challenge is to find ways to match supplies with the people they need in the city chain along this extension of the Guadalpe River.

This feeling is echoed throughout the region. At a press conference on Tuesday morning, the mayor of Kerrville Joe Herring Jr. The city works on a new way to deal with donations to respond to disasters.

“We need a new system to deal with the world’s generosity,” he said.

Delivery operations in bee hills

While driving in the west along the 39th highway, Mr. Monsey and his friend embody this challenge. The road has been closed to regular traffic, so they maneuver their trucks – loaded with food, water and cleaning – previous emergency vehicles and home wreckage destroyed by flood water. Thick debns that horses have become one of the most reliable transportation to search for victims and survivors.

Once, luxury cypress trees are bent in complete harmony, divided and uprooting, prostration before cloudy sky.

The ends of the trees from the windows of the abandoned homes. The blankets and towels, which were burned by flood water and trees branches, now suspended dozens of feet. The boats and boats are folded around the branches along the side of the road.

Mr. Monsey only met the participating volunteers-Frank Hoover and Jack Campbell-before a week in the church men group, but since July 5, they were leading supplies in difficult neighborhoods along the 39th Highway. Initially, they could not reach anything. The situation has improved somewhat since then.

“We have a lot of resources at the present time, but we cannot reach them where you need to reach it,” he says.

They stop in the hills of hummingbes, which is a one -causing sub -division about 200 yards from Guadalobi. Green cycri trees usually block the river, but today it is easy to see via a broken mud and wood field.

For the population, the river is more secure than it was during the weekend last weekend.

David Sdearns stands next to a car, drinks water and watching volunteers help cleaning his home. A few days ago, his neck came out of the water.

He says, “But we are alive, and this is what matters.”

A few hours later, Mr. Monsi returns to Ingram with his volunteer colleagues. Their trucks are slightly lighter, but the trip taught them that many supplies – like paper towels – are no longer needed. They need to exchange some of this for the scraping, gloves, shoes and other cleaning supplies. They will continue to make running “no matter how late we need it,” he says.

In the sky of the head, the clouds began to twist, and the sunlight shines on the Guadalobi River. Warning from healthy floods is still valid locally, but the rain is not expected until the weekend.

“The rain will change the search and rescue operations.”

“But he will not deter us,” he added.