The rats scurried into the shed. Flinching at the sound of a horde of tiny claws scratching at the ground, Migdalia Mass Llorens kept vigil over her sleeping family huddled together under a single blanket. The 35-year-old mother of three couldn’t bring herself to join her kids in peaceful slumber. The hard floor and the rodents were bad enough. There was also the sinking awareness that her family may no longer have a home to return to that kept her up well into the night.

It was late September 2017, and Hurricane Maria had just roared through Puerto Rico. The catastrophic storm came just weeks after Hurricane Irma swept through the archipelago. When Maria hit, the family was sheltering inside their wooden house, which they had tied down with wire cables in the hopes it would hold. But the cables were no match for the 155 mph winds: In the middle of the night, the cords snapped and the roof flew off, letting in a deluge of rain. During the eye of the storm, the terrified family ran out the front door and to a tiny cinder-block shed still under construction on their farm. Torrents of water joined the rodents creeping in through holes in the structure.

In the daylight, the Mass Llorenses emerged to find their house flattened — one of many in the rural agricultural municipality of Las Marías, tucked high up in the Cordillera Central mountain range on the main island’s west coast, destroyed by the storm.

“When the storm passed, we went outside and realized we had nothing left,” said Mass Llorens in Spanish. They picked through the wreckage to gather what they could, before she and her husband moved their children into the half-built shed — meant to store farm tools and crops, not people. “We lost everything. We cried.”

Ricardo Arduengo / AFP via Getty Images

After shelter, hunger quickly became the biggest concern for Mass Llorens and her family. At first, she harvested the scores of breadfruit and bananas that had fallen from their trees during the hurricane. Then she salvaged tins of Spam and sausages, boxes of crackers, and bags of rice from the rubble of her home. They had scarce other options. The Category 4 storm had isolated their rural community from rescue and relief efforts. Landslides and floods washed away roads and downed trees, and mounds of debris blocked the routes that remained.

As the days bled into weeks, with both electricity and cell tower communications still offline, the Mass Llorens family passed the time by beginning the slow, arduous process of cleaning up their land. Piece by piece — broken kitchen chair by shattered dish — they methodically cleared the debris into heaping piles of trash.

Time itself soon became another thing to contend with: Some of their food started to spoil. The rats also seemed to be getting hungrier — and braver. Before nightfall every day, the family had to pile their cache of food on a rotted wooden table and fight them off by hand. It was then that Mass Llorens realized that help would be a long way off.

“I was afraid of having nothing, of running out of food… it was horrible,” she said. “The help just didn’t come. It just didn’t arrive.”

Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

What happened to the Mass Llorens family was part of the hunger and humanitarian crisis that engulfed much of Puerto Rico after Maria. It would take nearly a year for power to be restored to all residents, the longest blackout in U.S. history. The sheer destruction of the storm resulted in bottlenecks of emergency aid distribution, including issues like a shortage of truckers, the loss of virtually all cell communication, and extensive infrastructure damage. The government response to Maria was horribly unequal when compared to similar situations.

At the same time, the food and water shortages experienced by millions of Puerto Ricans were also linked to the island’s staggering rate of food insecurity that preceded the hurricane — and that still persist today. Roughly 41 percent of the population currently lives below the poverty line, and up to one-third is believed to be food-insecure — which is nearly four times the average throughout the continental U.S.

In the wake of Maria, many residents of Puerto Rico, especially those working to improve the archipelago’s local food system, began to think about hurricane preparedness differently. Because they weren’t able to rely on federal assistance, they decided to build their own prototypes of resilience, which didn’t just set them up to be ready for the next storm, but also set them up to live better everyday lives. Cooperatives, gardens, and school-based agricultural programs emerged to fill the gaps left by the government. Barter networks and local farmers markets have become increasingly popular. Mutual-aid kitchens and community-led supermarkets have also expanded their work, ramping up donations, surplus food, and partnerships with nearby producers. These projects aren’t just temporary disaster responses. They are models of long-term resilience and food independence. They are living blueprints of what food sovereignty could look like in Puerto Rico — and elsewhere.

Lester Jimenez / AFP via Getty Images

Today, as climate change supercharges what forecasters expect to be a brutal hurricane season — Erin, one of the largest, fastest-growing hurricanes on record, just narrowly missed Puerto Rico — the archipelago is facing a compound crisis: The Trump administration continues to eliminate and halt federal funding while wiping out the government’s workforce. Communities throughout Puerto Rico are now gearing up for the one-two punch.

“Puerto Rico’s food system does not exist in a vacuum,” said David Josué Carrasquillo Medrano, executive director of the San Juan-based nonprofit Planifiquemos who also served on the Department of Agriculture’s Equity Commission during the Biden administration. The “food-secure, climate-resilient, economically just” future of Puerto Rico, he added, “requires breaking the policy cage that has kept it vulnerable for too long.”

Mario Tama / Getty Images

Puerto Rico is overly reliant on imported food, which history shows can quickly spiral into a crisis of accessibility when a bout of extreme weather strikes, power is knocked out, and a group of islands home to more than 3 million people becomes entirely dependent on outside aid shipped in by sea and by air for survival. Many experts say that this situation was spurred by one pivotal policy: the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, colloquially known as the Jones Act, which bars international maritime vessels from shipping goods between U.S. coasts — meaning that merchandise traveling between U.S. ports must be delivered on vessels owned and operated by Americans. Some analysts have argued that this law has had the effect of ticking up shipping costs and making it less possible over time for Puerto Rican farmers to compete with U.S. mainland food manufacturers. Others have questioned the true impact of the Jones Act on the archipelago’s food sovereignty. A 2012 report by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York noted that “to the extent that it inhibits free trade, the Jones Act does indeed have a negative effect on the Puerto Rican economy, although the magnitude of the effect is unclear.”

The Jones Act, however, wasn’t the only policy to contribute to Puerto Rico’s broken food system. In the 1930s and ’40s, a series of local economic regulations directed at the sugar cane industry led to the demise of what was once the archipelago’s most common agricultural product and its largest source of revenue. From there, the U.S. territory’s reliance on imports steadily climbed. In the 1980s, Puerto Rico grew around 45 percent of its own food; today that number is around 15 percent.

Declining local agricultural production only deepened Puerto Ricans’ dependency on external supply chains. From 1992 to 2007, the number of farms decreased by 30 percent, the amount of land being farmed decreased by 33 percent, and total livestock and poultry products sold dropped by nearly 19 percent. The agriculture sector also lost roughly a third of workers. In 2006, an economic recession gripped Puerto Rico. Nearly 20 years later, that recession has not abated.

Shortly after Hurricane Maria, Republican senators John McCain and Mike Lee introduced a bill seeking to repeal the Jones Act, which they said was hindering the island’s recovery process by limiting the flow of maritime emergency aid shipments. McCain, who had long championed ending the policy, called it an “antiquated, protectionist law that has driven up costs and crippled Puerto Rico’s economy.”

Though McCain and Lee’s legislative efforts were unsuccessful, President Donald Trump temporarily suspended the law at the request of Puerto Rico’s governor, Ricardo Rosselló. The suspension expired in early October 2017, just two weeks after the storm, and made little difference for Puerto Ricans. According to a Brookings Institution report from that year, the law, and its waiver, didn’t contribute to the larger relief issues at play; there were other, more consequential factors — “The key problems, including insufficient and delayed federal resources, and a lack of means to distribute supplies on the island, have nothing to do with the Jones Act.”

Joe Raedle / Getty Images

For nearly a decade before the storm, Owen Ingley and his wife, Paula Paoli Garrido, ran a nonprofit organization called Plenitud PR, which maintained a small, sustainable farm and advocated for a localized network of agricultural producers throughout Las Marías. The cataclysmic hurricane set the organization down a new path.

They distributed emergency water filtration stations, installed rainwater harvesting tanks at elderly residents’ homes, and collaborated with local doctors to hold health clinics. The experience sparked a new awareness for Ingley — that something was missing. The Las Marías community needed a physical place, stocked with critical recovery resources, where they could go to get support after a disaster like a hurricane.

“It was a really defining moment for our organization,” said Ingley. “There’s some comfort in having hot, prepared, healthy meals after a hurricane, having access to a warm plate of food, cooked with love, with healthy, local ingredients. I think there’s a health benefit, and I think there’s an emotional, psychological benefit to it also.”

Meanwhile, life became exceedingly difficult for Migdalia Mass Llorens and her family. About a month after the storm, her youngest son, José, was stung by a scorpion. Mass Llorens herself contracted leptospirosis, a rat-borne disease. For roughly 60 days, the breadfruit and bananas available on the farm and a dwindling stash of canned goods were about all they ate. When first responders and government officials finally showed up, nearly three months after Maria made landfall, hand-delivering boxes of bottled water and ready-to-eat meals, Mass Llorens felt a sense of overwhelming relief. Then the frustration hit. She wondered: Why had it taken them so long? Why was her community, her family, left to fend for themselves? In that moment, she knew she never wanted to be in that position — waiting for help that didn’t come — again.

As time went on, life slowly began to retain some normalcy — enough, at least, for José to be sent back to his elementary school. One day, Paoli Garrido, of Plenitud, came to the school to try to make connections with local farmers. José offered her a breadfruit from his parents’ stash. That prompted the team at Plenitud to reach out to Mass Llorens to see if she and her husband, Juan, were interested in participating in the group’s agricultural cooperative.

Over the next year or so, Mass Llorens and Plenitud continued to talk about how they could work together. Mass Llorens was inspired by the concept of community-powered resilience. Plus, she needed to bring in a paycheck after Maria had wiped out their harvest, so in 2020 she eventually signed on to help start and run the community kitchen.

The Plenitud team was still in search of a site to work from. First, they collected signatures from a little over 200 residents in Alto Sano, a petition they shared with the municipality to permit the nonprofit to launch the kitchen in an abandoned school building. The town leased the half-acre lot to the organization for $120 — paid monthly, $1 at a time over a decade. Plenitud then got to work finding a mix of grant and philanthropic funding that would keep the kitchen open year-round, so that it could ensure food security for some of the area’s most vulnerable residents and double as a disaster resilience hub when the next storm swept through.

Plenitud set itself up to receive donations of surplus nonperishables from a nearby food bank and launched an on-site community garden with crops like lettuce, cilantro, herbs, and peppers. The team secured funding to pay farmers for fresh produce such as breadfruit and jackfruit, with the goal to freeze it all and store bulk amounts of it ahead of hurricane season every year. Staffers set up a rainwater filtration system that could store thousands of gallons of potable water and fundraised to buy dozens of at-home mini filtration systems. They also partnered with other nonprofits to establish off-grid solar to help power the site and acquire solar lights for folks with mobility limitations that would prevent them from evacuating or reaching the center.

By 2021, Plenitud was ready to open the new facility. It was part kitchen, part food vault, and part community gathering place. They would call it La Cancha Sana — named in honor of the property’s basketball court, or una cancha, and the neighborhood, Alto Sano.

“People saw after Hurricane Maria that the local government just doesn’t have enough resources and enough efficiency to be able to effectively respond,” said Ingley. “We need to come together and be prepared to jump in ourselves. …El pueblo salva al pueblo. The people save the people.”

La Cancha Sana had its first big test run when Hurricane Fiona barrelled through Puerto Rico on September 18, 2022, once again knocking out power, triggering mudslides and flash floods, and destroying roads. Just after the storm, a ship sailing under the flag of the Marshall Islands attempted to deliver about 300,000 barrels of fuel to help with the recovery, but it was initially unable to dock because of foreign vessel restrictions mandated by the Jones Act. (It docked several days later after the Department of Homeland Security granted a Jones Act waiver.)

By then, Plenitud had stored thousands of gallons of filtered rainwater and stockpiled nonperishable food and fresh vegetables from their nearby farm. They had also acquired hundreds of gallons of emergency propane. Unlike after Maria, Mass Llorens and her family had a safe haven; a space to eat, get water, and gather with their community after another storm tore through their lives. She spent the next 21 days at La Cancha Sana cooking, day in and day out. She made plates of rice and beans, cooked squash, guacamole, and fried plantains, a welcome source of nutrition for rural communities like hers still without power. Those days, Mass Llorens said, were a blur.

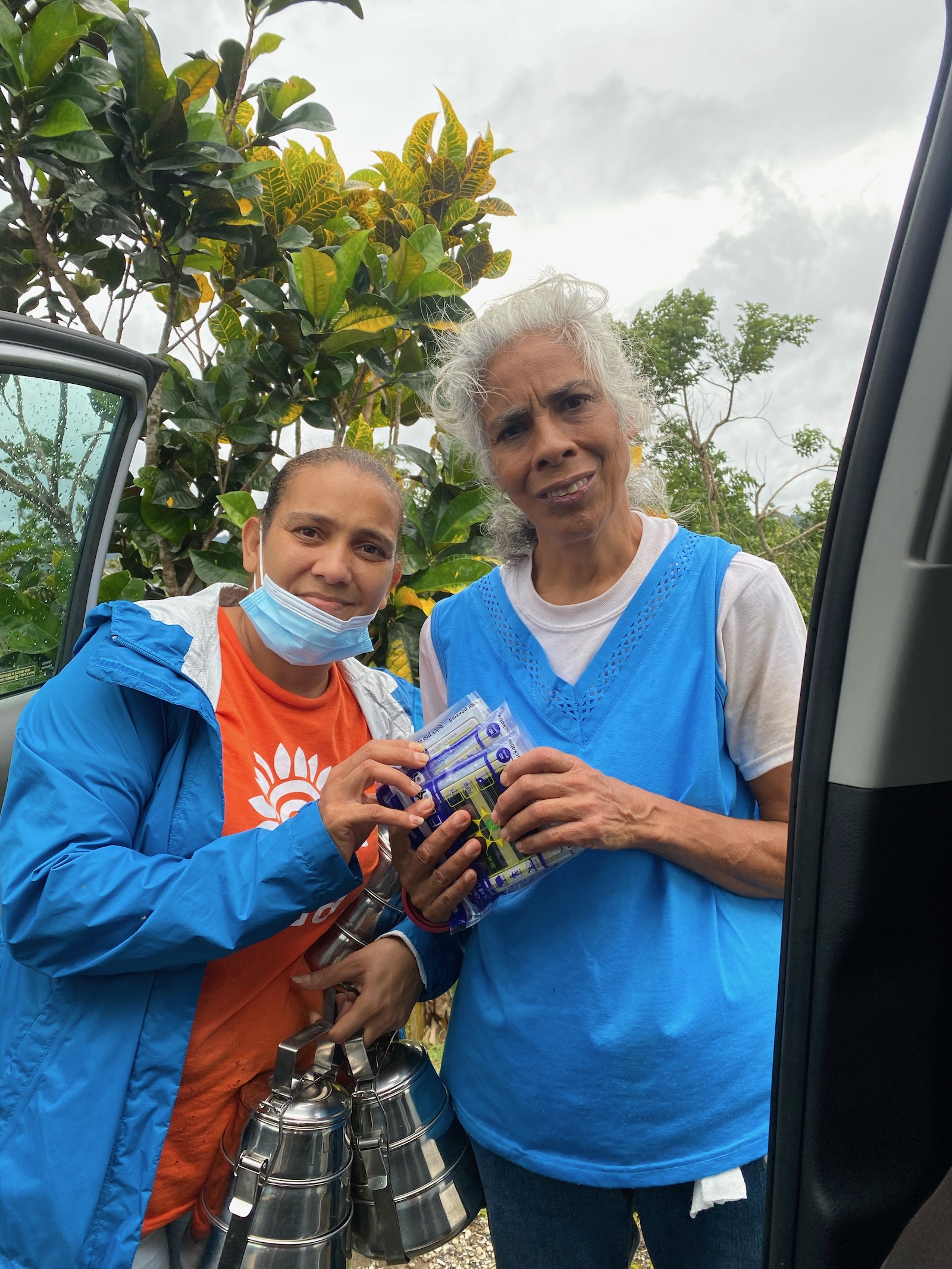

The rest of her family worked with the Plenitud team to deliver food and rainwater harvesting devices to homes in the barrio. They also got the word out: La Cancha Sana had power, and everyone was welcome. Some of Mass Llorens’ colleagues went down to the local farms to help the producers salvage produce like avocados, plantains, and breadfruit that could no longer be sold in markets or shipped anywhere. As the news about La Cancha Sana spread, people filtered in from nearby barrios, too. By the time the power had been restored, three weeks after the storm, they had served around 2,500 meals.

“In hurricanes, in moments of emergency, in the place where we are, a very rural place, we are far from the coast, from the cities. In el campo — the rural areas — we’re left for last,” said Mass Llorens. “Communities really need this kind of support because the government just won’t show up in the way you need. We can’t wait for help to come from outside.”

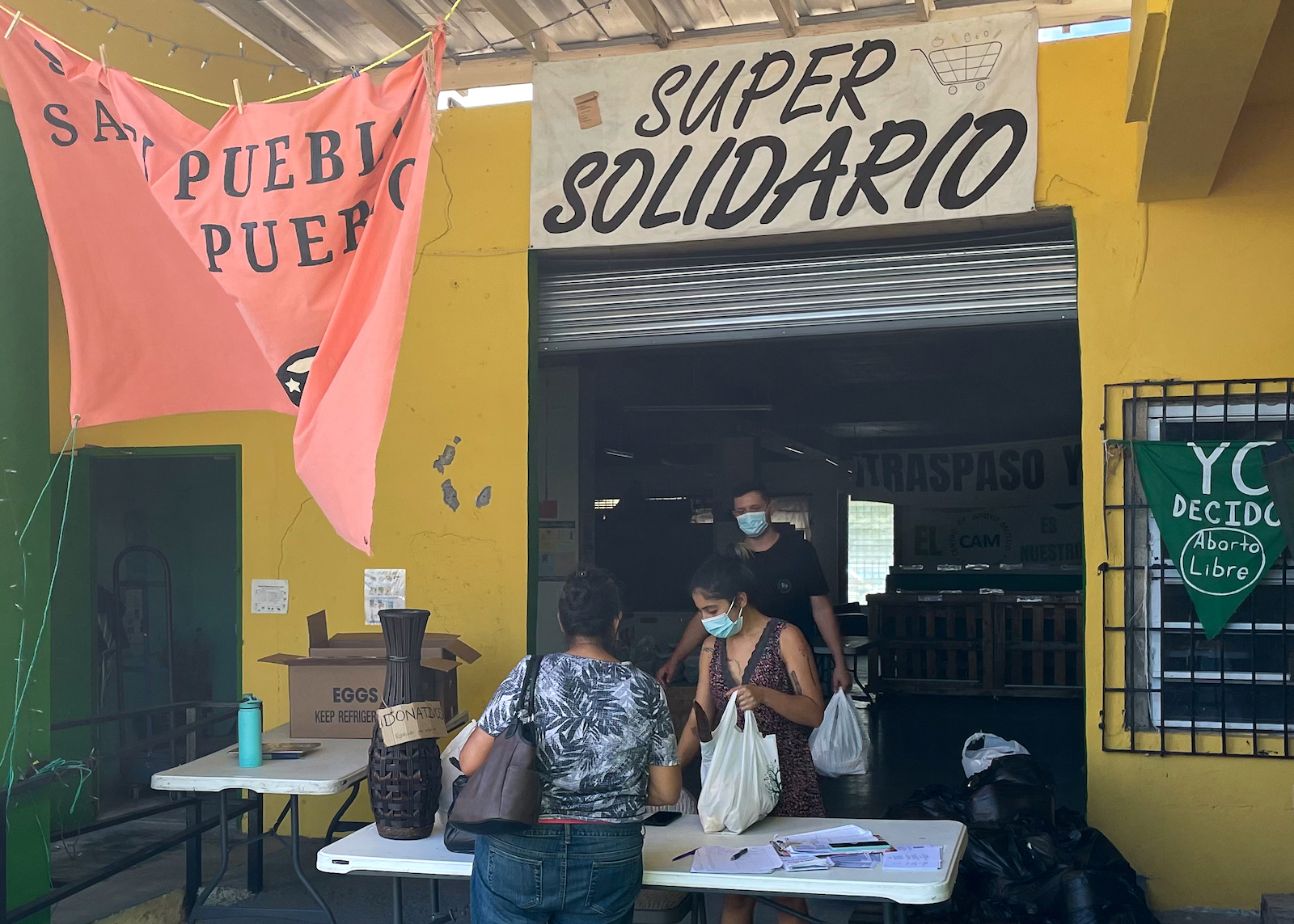

On the central-eastern side of Puerto Rico’s main island, in the densely populated city Caguas, another resilience center jumped into action as Fiona thundered through. The first iteration of Giovanni Roberto Cáez’s community kitchen was cobbled together in days after Hurricane Maria. Following Fiona, Comedores Sociales de Puerto Rico was running a full-scale mutual aid operation in its own building.

Every Tuesday for the next month, hundreds of Caguas residents showed up to take home free rice, beans, and canned goods in addition to fresh produce sourced from local farmers. Instead of being given pre-packed food, people were encouraged to choose what they needed or wanted, and invited to participate as a volunteer or donate to the effort if they could.

Unlike Plenitud, and most traditional charitable food businesses, Comedores Sociales doesn’t rely on government money. Instead, it receives philanthropic support, sells merch, hosts concerts, offers catering services, and twice a year hosts community fundraising dinners. “Food is not only a biological need,” said Roberto Cáez. “It’s a cultural need, it’s a social need. Because food brings us together. It puts us at the same table, organizes our communities to harvest together.”

It is also a matter of politics, he continued. “Its loss, and land, and power, and the companies who control the food. Who has the power to decide those things. And who does not.”

The lack of coordination from governmental agencies that followed Hurricane Maria led many Puerto Ricans to come to the conclusion that they were on their own, said University of Central Florida disaster sociologist Fernando Rivera — which he said may have, in an ironic twist of fate, prepared them for the reality of sweeping federal disinvestment unfolding now across the U.S.

“There’s a redefining of what the role of the federal government is in everyday life of our people. There’s a profound discussion now of who takes the realms of emergency management, or emergency preparedness,” said Rivera, who has studied disaster response and preparedness in Puerto Rico and Florida. “In a sense, that predisposition of the horrible things that happened after Hurricane Maria actually activated these communities and brought about this knowledge of what we need to do.”

But Rivera warns that if community-led programs like these end up being successful, and are privately funded, then it could serve as an incentive for federal agencies to retreat even further from the fundamental duties of the government.

The Trump administration has imposed severe cuts on the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the speed at which the government processes declarations of major disasters has noticeably slowed down. Trump also terminated $4.5 billion in FEMA grants that helped communities prepare for future disaster damage, though a federal judge recently barred the administration from doing so. This almost certainly does not bode well for Puerto Rico, said Rivera.

The second Trump term has also resulted in direct cuts to federal funding pots going to Puerto Rico, including the end of roughly $10 million that backed two programs supporting farmers and forest stewards with technical assistance and workforce development tools: Smart Ag Puerto Rico, created to support smallholder coffee and cacao farmers, and conservation initiative Puente Forestal. The former is on hold until further notice; the latter has been cancelled outright. The administration’s cancellation of federal grants supporting food pantries and local food systems has also sparked concern among community organizations that the reductions will have a knock-on effect on Puerto Rico’s disaster recovery efforts — similar to the shortages experienced by food banks responding to the recent floods in Texas. Puerto Rico is also one of three U.S. jurisdictions excluded from the USDA’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. Instead, the archipelago receives a capped annual block grant through the Nutrition Assistance Program, or NAP, which does not adjust to inflation, population growth — or, notably, disaster impacts.

Even groups like Comedores Sociales that aren’t federally funded are still confronting the consequences of Trump’s considerable policy shifts. Since January, private groups funding the organization’s mutual aid center have begun scaling back their donations, shortening the terms of their agreements, and some individual donors have even suspended their contributions. Comedores Sociales has a runway through the end of next year, but founder Roberto Cáez doesn’t know whether it will have the funding needed to sustain operations beyond then.

In the case of La Cancha Sana, the federal funding roller coaster is also exacting a toll. Although none of its contracted grants have yet to be canceled, the group gets much of its federal funding through AmeriCorps, which has faced significant cuts in the last eight months. The future of several of their pending grant proposals is also now unclear amid the administration’s slashing and burning of climate justice programs they once relied on for their work.

Ingley says his team is taking it one day at time; the main priority right now is continuing to stockpile food and water so Plenitud can best be prepared to feed the community this hurricane season. Some 4,000 gallons of water are currently stored in cisterns at La Cancha Sana, alongside more than 3,000 servings of rice and hundreds of pounds of canned beans, dried nuts, and legumes. Ingley worries it won’t be close to enough.

“I am concerned about facing an even greater need in the event of a hurricane like Maria,” he said. “There’s a sense of burden about not being able to do enough. Our capacity is staying about the same, and the need is just growing more.”