Society

/

September 16, 2025

The 160 members of the university notified that their names were forwarded to the DOE’s Office for Civil Rights were not informed of any specific allegations against them.

The 160 members of the university notified that their names were forwarded to the DOE’s Office for Civil Rights were not informed of any specific allegations against them.

“We’re in Kafka-land,” observes Judith Butler, the internationally renowned philosopher who for decades has been one of the most prominent members of the University of California, Berkeley, academic community. This month, Butler learned that they were one of 160 faculty members, students, and staffers at the university whose names had been shared with the Trump administration as part of a federal investigation targeting “alleged antisemitic incidents.” A notification from the university provided no details of specific allegations. Butler, who is one of many Jewish scholars sharply critical of the Israeli government’s assault on Gaza, wrote a stirring response. They shared it with The Nation, along with a brief account of their exchange with UC Berkeley’s chief counsel.

On September 4, 160 members of the University of California, Berkeley, community received a letter from the university’s chief counsel, David Robinson, informing us that files containing our names were forwarded to the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights in response to its investigation of antisemitism on college and university campuses. When I received the notification, I had not been aware of how many of us were included in these files since the UC Berkeley had been assured the university community that it would engage in only minimal compliance. At the time I was writing about Kafka and the law, so I wrote to the chief counsel about how my work and his missive appeared to converge. Below is a slightly edited version of the e-mail I sent to him and UC Berkeley’s Legal Offices on September 7.

* * *

Dear David Robinson,

I am not sure if we have met, but I wanted to introduce myself as a retired faculty member, presently engaged in grant-funded activity at UC Berkeley and appointed as a Distinguished Professor in the Graduate School. In my Comparative Literature seminars over many years, I taught seminars on Kafka and the law. They very often focused on the way that the suspension of due process and the normalization of indefinite detention were cast in fictional terms that resonate with actual legal practice. As you may know, Kafka was not only a great German-language writer, but a member of the Czech Jewish community who was engaged in debate on the traditions of Jewish law. Trained as a lawyer, he spent most of his adult life adjudicating claims of physical injury suffered by workers on the job. He made sure procedures were honored, and that hearings were fair. In the evenings, and especially on Sunday, he tried to write. His parables, in particular, investigate whether or not we can still expect justice from the law, or whether legal process diverges so dramatically from the path of justice that we can only now tell stories about how the expectation of justice is vanquished by legal proceeding. That is the subject of my present scholarship, and I hope to have a completed manuscript by the end of 2025.

Some of what I am arguing can be found most dramatically, however, in his well-known novel, The Trial. That novel begins with an office worker named K who is awakened one morning by two gentlemen who claim to represent the law, but they seem to be from his place of employment. Their status is ambiguous. In any case, they inform him that there is an allegation against him, and he reasonably asks: what does the allegation consist of? They explain that they cannot say, and it actually seems that they do not know. They are ominous emissaries who do not know or will not say what the allegation against K actually is. When he asks them how he can discover the substance of the allegation, they send him down various paths in a city that resembles his own Prague to a building whose doorways are impassable. He tries in vain to find someone who can tell him of what he has been accused, but he can find no one. He is supposed to prepare for a trial, but how can he do this without knowing of what he is accused? After many pages of waiting and inquiring without result, it becomes clear that this process of waiting to know what has been said against him is the trial itself. He is waiting for a fair procedure to start, but it never does.

One of K’s problems is that he still believes that due process and established procedures governing complaints, grievances, and accusations are in place, that the right to know and to counter the charges against him will be part of that procedure, and that his own defense will be taken into account before any action is taken. He tries to find legal counsel, but the lawyers he meets are equally confused by the arbitrary and ominous character of the process.

Current Issue

As someone trained in the US legal tradition, you will recognize that K is hopelessly expecting that he will be afforded the equivalent of protections offered by the 6th and 14th Amendments of the Constitution, namely the right to a lawyer, the right to an impartial jury, and the right to know who your accusers are and the nature of the charges and evidence against a person charged with wrongdoing. But these protections are doubtless also familiar to you as they are the stated policy of the OPHD (the Office for the Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination). That policy is the following:

For complaints of any form of discrimination and harassment, OPHD follows the resolution process that is established in the UC systemwide policy and corresponds to campus implementing procedure. These processes are developed so that every case is reviewed and addressed in a consistent way. Our aim is to work with those who bring allegations of misconduct, those who respond to those allegations, and anyone else who contributes information to the fact-gathering process, in a way that is as transparent and respectful as possible for everyone involved. OPHD’s role focuses on delivering a fair and objective resolution process, as opposed to supporting one party over another.

Indeed, this policy is meant to make sure that people in K’s position are contacted, informed of the complaint, and invited to a meeting and apprised of the resources available to them, including “complaint resolution” that does not involve engaging the court system. The warning in your letter that there may be a need for the “production” of new materials does not indicate whether you are asking for disclosure of additional information or additional forms of unfounded and unadjudicated allegations.

Of course, I am not K, but I find myself uncannily identified with his predicament. For in the letter you have sent you and your offices have informed me only that you have sent “a file or report related to alleged antisemitic incidents” that includes my name. Two aspects of this communication stand out to anyone who has read Kafka’s work. The first is that you imply, without stating it, that I have been accused of antisemitism or that my name is associated with an incident of that kind. But you are also actually more careful since you say that the incident of antisemitic harassment or discrimination is “alleged,” which means simply that the allegation was neither reviewed nor adjudicated but left to stand on its own.

Instead of treating the report according to procedure as you are obligated to do under both US constitutional law and University of California policy, you forward the allegation, unadjudicated to an office of the federal government. Whether or not the allegation is fair is of no consequence, it seems, for there has been an allegation, and that appears to be sufficient to forward my name to the DOE’s Office for Civil Rights (clearly not my civil rights), where it will be on a list and used in whatever way that office and that government deems appropriate.

Will I now be branded on a government list? Will my travel be restricted? Will I be surveilled? Have you no compunction about submitting the names of “members of the UC Berkeley community” as you address us in your form letter, without having complied with basic rules of due process institutionalized in both US law and UC policy? In addition, students on visas and adjunct faculty unprotected by academic freedom are among those whose names were passed along. As we know from actions taken against students at Columbia, Harvard, and Tufts, to name a few, they are all potentially at risk of being detained, deported, expelled, harassed, fired, even abducted on the street.

I am a relatively privileged person who will find a way to survive whatever actions the government may take against me, but the idea that you have subjected a number of faculty, staff, and students to widespread surveillance is a breathtaking breach of trust, ethics, and justice. I urge the OPHD to insist upon its powers and refuse to cede to federal demands. I also urge the OPHD to take up a principled position in favor of due process, fair review, and the procedures that has guided UC Berkeley prior to this unprecedented intervention into what should be a matter of self-governance. Let us not sacrifice our integrity as an institution to legalistic forms of state bullying and extortion.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Like K, I would like to think that we live in a world in which allegations are not treated as true until subject to proper procedures, and that we do not jeopardize an individual by sending an unfounded and unadjudicated allegation to the federal government at this time in human history. Perhaps I am a fool and can only live in the world of parables. Lucky that I still have my books. But it cannot be utterly foolish to resist injustice when you so clearly see it, as, I presume, you must.

Sincerely,

Judith Butler

Donald Trump wants us to accept the current state of affairs without making a scene. He wants us to believe that if we resist, he will harass us, sue us, and cut funding for those we care about; he may sic ICE, the FBI, or the National Guard on us.

We’re sorry to disappoint, but the fact is this: The Nation won’t back down to an authoritarian regime. Not now, not ever.

Day after day, week after week, we will continue to publish truly independent journalism that exposes the Trump administration for what it is and develops ways to gum up its machinery of repression.

We do this through exceptional coverage of war and peace, the labor movement, the climate emergency, reproductive justice, AI, corruption, crypto, and much more.

Our award-winning writers, including Elie Mystal, Mohammed Mhawish, Chris Lehmann, Joan Walsh, John Nichols, Jeet Heer, Kate Wagner, Kaveh Akbar, John Ganz, Zephyr Teachout, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Katha Pollitt, Kali Holloway, Gregg Gonsalves, Amy Littlefield, Michael T. Klare, and Dave Zirin, instigate ideas and fuel progressive movements across the country.

With no corporate interests or billionaire owners behind us, we need your help to fund this journalism. The most powerful way you can contribute is with a recurring donation that lets us know you’re behind us for the long fight ahead.

We need to add 100 new sustaining donors to The Nation this September. If you step up with a monthly contribution of $10 or more, you’ll receive a one-of-a-kind Nation pin to recognize your invaluable support for the free press.

Will you donate today?

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Sysco’s market dominance means that something essential is being lost. As local businesses fade away, a sense of a distinct regional and local identity disappears with them.

Austin Frerick

The university has largely complied to the government’s efforts to reshape higher education as critics on campus question the role of neutrality altogether.

StudentNation

/

Arman Amin

A conversation with the author about her new book, “From the Clinics to the Capitol: How Opposing Abortion Became Insurrectionary”.

Amy Littlefield

The right-wing influencer did not deserve to die, and we shouldn’t forget the many despicable things he said and did.

Joan Walsh

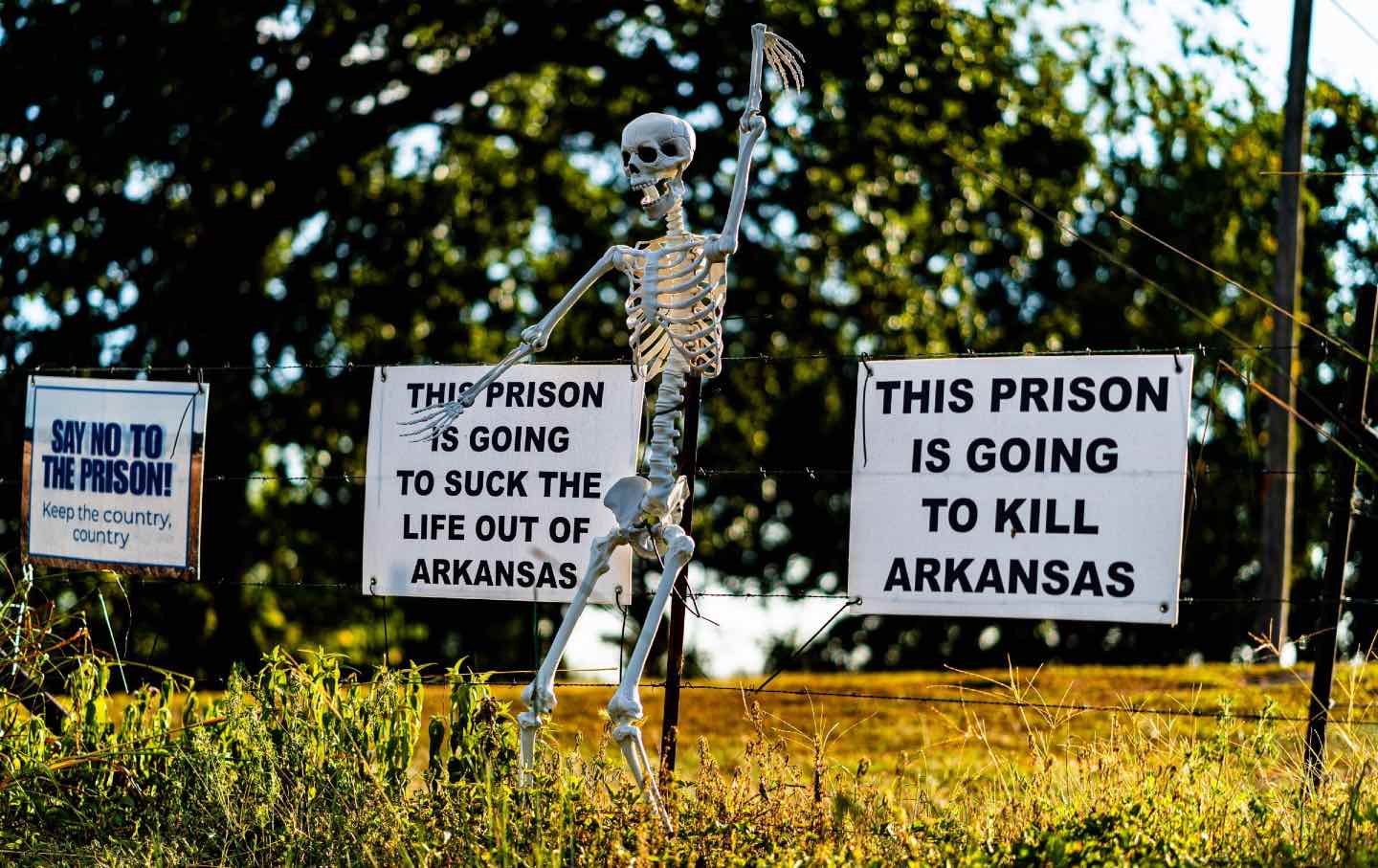

A secretive plan for a new state lockup angered people in a deep-red corner of rural America—and changed how some see incarceration.

Lauren Gill

A conversation with P.E. Moskowitz about the chemical imbalance theory of depression, the false schism between prescription and recreational drugs, and collective psychic pain.

Emmeline Clein