Tim Mansell

Tim MansellKayla first experienced fentanyl when she was 18 years old, growing up in North Carolina.

“I felt like I was literally amazing. The voices in my head completely silenced me. I was instantly hooked,” she recalls.

The little blue pills Kayla became addicted to were likely made in Mexico, then smuggled across the border into the United States — a deadly trade that President Donald Trump is trying to stamp out.

But drug gangs are not pharmacists. So, Kayla never knew how much fentanyl was in the pill she was taking. Will there be enough synthetic opioids to kill her?

“It’s scary to think about,” Kayla says, thinking about how she could overdose and die at any moment.

In 2023, there will be more than 110,000 drug-related deaths in the United States. The advance of fentanyl, which is 50 times more powerful than heroin, seemed unstoppable.

But then came the amazing transformation.

In 2024, the number of fatal overdoses across the United States will decrease by about 25%. This means nearly 30,000 fewer deaths – and dozens of lives saved every day. Kayla’s home state of North Carolina is at the forefront of this trend.

Why have fatal overdoses declined so sharply?

One explanation is a commitment to harm reduction. This means promoting policies that prioritize the health and well-being of drug users rather than criminalizing people – recognizing that drug use in the age of fentanyl often ends in death from overdoses.

And in North Carolina, where Kayla still lives, and where overdose deaths have now dropped by a staggering 35%, harm reduction strategies are well developed.

Kayla no longer uses street drugs. She is a client of the innovative Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program in Fayetteville. It’s a partnership between city police and the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. Together, they work to keep drug users away from crime and put them on the path to recovery.

Tim Mansell

Tim Mansell“If someone is stealing from a grocery store, we look at their criminal history. We often see that the crimes they commit seem to fund the addiction they have,” says Lt. Jamal Littlejohn.

This may make them candidates for the LEAD program, which means they can get support to address their addiction, and they can start thinking about safe housing and employment.

LEAD supporters say it’s not about going easy on crime. Drug dealers still go to prison in Fayetteville. “But if we can get people the services they need, it gives law enforcement more time to deal with bigger crimes,” says Lt. Littlejohn, who watched his sister struggle with substance use disorder.

Kayla has thrived. She is now a long way from the days when she used prostitution to fund her fentanyl use. As part of Operation LEAD, her criminal record was expunged. She recently graduated as a Certified Nurse Assistant and now works in a residential home.

“It’s the best thing ever. This is the longest I’ve ever been clean,” she says.

Therapy was crucial to Kayla’s recovery. She had been taking methadone for about a year when she told her story to the BBC. “This keeps me from coming back,” she thinks.

Methadone and buprenorphine are medications used to treat opioid use disorder. It stops cravings and stops painful withdrawal. Nationally, the treatment has played a role in cracking overdose death statistics.

In North Carolina, this program is a game-changer: more than 30,000 people are enrolled in the program in 2024, and the numbers will rise in 2025.

“You’re still playing Russian roulette, but your chances are getting better.”

Tim Mansell

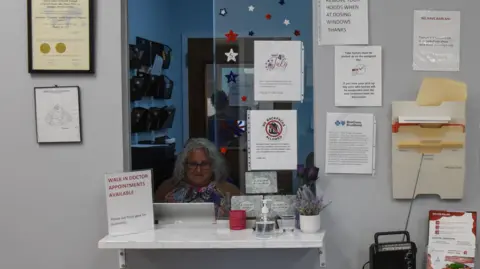

Tim MansellAt 9 a.m. at a Morse clinic in the state capital of Raleigh, two or three people are waiting their turn at the front desk.

“The busiest time is 5:30 a.m. to 7 a.m., before work,” says Dr. Eric Morse, an addiction psychiatrist who runs nine medication-assisted treatment (MAT) clinics in North Carolina. “Most of our employees are working, and once they wake up, they come to work on time every day.”

The clinic runs a carefully controlled process. After patients log in, they are called to the dosing window to receive their prescription. They are in and out in minutes.

They will be randomly tested for illegal drugs. Dr. Morse says about half of his patients still struggle with opioids bought on the street, but he doesn’t see this as a failure.

“Maybe you’re using it once a week and you’re used to using it three times a day… and you’re still playing Russian roulette with fentanyl, but you’ve taken a whole bunch of bullets out of the chamber, so your survival rate goes up significantly,” Dr. Morse says.

This is damage limitation. So, instead of being kicked out of the treatment program, patients who receive a positive drug test result receive additional support and counseling. Dr. Morse says 80-90% will eventually stop using street drugs altogether. Over time, many will stop taking their medications as well.

Discuss abstinence

Tim Mansell

Tim MansellNot everyone thinks this is the right approach.

Mark Bliss is a Republican member of the North Carolina House of Representatives who worked full-time as a paramedic. He points out that illicit drug use begins with choice.

He does not believe in harm reduction. In particular, he is against treating opioid use disorder with medications like methadone or buprenorphine.

“You’re replacing one addictive product with another addictive product,” he says. “If you have to take them to stay clean, they’re still addictive. We have to figure out how to get people to where they can do better — we can’t leave them on drugs forever.”

He favors abstinence treatment programs, when drug users go “cold turkey.”

But there is opposition from health professionals in North Carolina.

“I think there are multiple paths to recovery,” says Dr. Morse. “I don’t hate abstinence-based treatment — except when you look at the medical evidence.”

References Dr. Morse Yale study from 2023 Analysis of the risk of death for opioid users in a treatment program compared to people not in treatment. The study indicated that a person in abstinence treatment is as likely — or more likely — to suffer a fatal overdose as someone who was not in treatment and continued to use street opioids such as fentanyl.

Aside from treatment, there is another medication that helps.

Naloxone is widely available and is used as a nasal spray. It reverses the effect of an opioid overdose, helping a person breathe again. In North Carolina in 2024, it was administered more than 16,000 times. Potentially 16,000 lives could have been saved, and these are only the overdose reversals that have been reported.

“This is the closest thing to a miracle drug we can imagine,” says Dr. Nabaron Dasgupta, a street drug scientist at the University of North Carolina.

Tim Mansell

Tim MansellMany users of drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, and heroin want to know that what they are taking will not kill them. Some people use test strips to check for the presence of fentanyl, because they know it is involved in many fatal overdoses.

But the strips don’t identify all potentially harmful substances. Dr. Dasgupta runs a national drug testing laboratory. Users send him a small portion of their drug supply via local non-profit organizations.

“We have analyzed nearly 14,000 samples from 43 states over the past three years,” he says.

Generational shift

Testing drugs for potentially dangerous additives is an additional weapon in the harm reduction armoury. Dr. Dasgupta believes another reason for the decline in overdose deaths in the United States is that young people are avoiding opioids like fentanyl.

“We are seeing a demographic shift,” he says. “Generation Z is dying of overdoses much less frequently than their parents or their grandparents’ generations did at the same age.”

Dr. Dasgupta isn’t entirely surprised that people in their 20s are turning away from opioids. Shockingly, four in 10 American adults know someone whose life ended in an overdose.

It was this epidemic of death, sparked in the 1990s by the prescription of opioids, that prompted North Carolina’s former attorney general – now the state’s governor – to act against powerful corporations that profit from the dark spiral of addiction in which many Americans live.

Josh Stein liaised with his counterparts in other states and took a lead role in coordinating legal actions against opioid manufacturers, distributors and retailers.

Tim Mansell

Tim Mansell“There was a Republican attorney general in Tennessee, and I’m a Democrat in North Carolina…but we all care about our people and we’re all willing to fight for them,” Stein says.

The result, after years of intense negotiations, was an opioid settlement worth a total of around $60bn (£45bn). This is money that huge companies have agreed to pay to US states, to be used to “reduce the opioid epidemic.” North Carolina’s share is about $1.5 billion.

“It should be spent four ways — drug prevention, treatment, recovery, or harm reduction,” says Governor Stein. “I think that’s transformative.”

Meanwhile, funding from the national government is uncertain. The cuts to Medicaid included in President Trump’s big, beautiful law could have a huge impact on this area.

At Morse Clinics in Raleigh, 70% of patients rely on Medicaid. If they lose health insurance, will they end treatment and be more likely to die from overdose? Although North Carolina’s drug death statistics seem optimistic, thousands of people are still dying — and the state’s Black, Indigenous, and nonwhite populations have not seen the same rates of decline.

Still other states have seen a slower rate of decline in fatal overdoses – including Nevada and Arizona.

Tim Mansell

Tim MansellNo one feels complacent. At least Kayla.

In the grip of fentanyl for three long years, she never overdosed, but she had to save her friends. Kayla’s parents didn’t know what to do with her.

“They kind of abandoned me, thought I was going to die,” she recalls.

Kayla credits Charlton Roberson, her damage reduction mentor, as instrumental in her recovery. Her goal now is to gradually taper off methadone use and eliminate medications and drugs. She also wants to find a job at the hospital.

“I feel more alive than I ever did when I was using fentanyl,” she says.

If you are affected by the issues in this story, help and support are available via BBC Action Line.