Flashs of brilliance: early photography genius and how art, science and history have shifted Anika Burgis Ww norton (2025)

As a person who spent a profession in the perception of science, Flashes of brilliance I felt a love message to the power of the photo. This beautifully written book, by the writer and photo editor Anika Burges, is a thoughtful, personal and smart reflection on how the images make more than just a scene documentation.

Will Amnesty International strengthen scientific photography? There is still time to create an ethical code

Besides the wonderful examples of direct efforts to take pictures of society, the book takes well the double role of the scientific image – as a tool for discovery and a means of communication. The reader begins to understand that photography in general, especially in science, is not just an illustration, but rather a survey. Sometimes, Borgis clearly describes, it is revelation.

Through a series of convincing stories and visual examples, the author reminds us that the image can crystallize a complex idea in a way that no series of words at all can. It is a celebration of “Aha” moments visible. These images wake up on social issues and phenomena that we never knew.

Yaqoub Reyes says about the dull circumstances of people who live in housing on the lower eastern side of New York City around 1889 than any text describing the situation. Using flash powder to add light to exposure, it can reveal the details of these dark spaces usually and those who inhabit them.

Jacob Rice acquired the bad conditions of people who live in New York City around 1900, such as these children who sleep on warm steam.Credit: Granger/Historical Pictures Archive/Governance

Reality processing

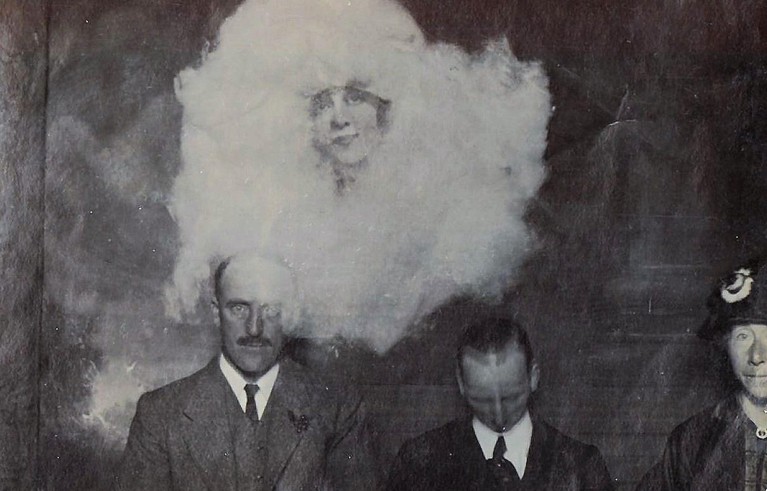

Burgis is not ashamed of challenges, either – recognition of the ease of misinformation or manipulation. Even from the beginning, some photographers used a technique to combine negatives in the printing process to create unrealistic scenarios. In the early seventies of the nineteenth century, édouard Buguet used this way to include a transparent “spirit” over people in its forms to enhance the idea that the dead could communicate from behind the grave. Many viewers believed that the soul was real; Only in 1875, Buguet admitted that the photos were fake.

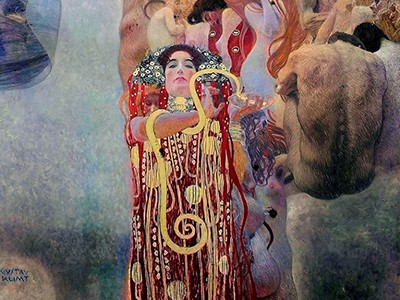

How artificial intelligence expands the history of art

The balance between clarity and accuracy is something that I dealt with throughout my career, and it is refreshing to see this problem directly. These days, at least in science, any careful manipulation must be considered and reported.

Another example came as a surprise. I never get tired of studying the beautiful Eadweard Muybridge series of fixed images that show horses in the movement. His photos from the late 1970s clearly show that at different moments in jogging, all four horses leave the Earth at the same time – a fact that was not known until then. What was new to me was to read how “replace or miss and certain groups of images, which naturally call for their scientific benefit.” Marta Brown’s historian also argued in her book in 1992 Time photography: “Under the guise of presenting the scientific truth to us,” Moyberbridge “like any artist chose and arranged his choice in the personal truth.”

Craig and George Faloner produced several “spirit” images in the twenties.Credit

For those of us in scientific communication, this warning is necessary. Just because the image is beautiful, it does not mean that it tells the entire story. However, I do not want to completely deduct his contribution to the moment of “Aha” in science. We were informed of the process (just as NASA scientists do when they color astronomical images) and why he did what he did would have helped us to look at the study as an authentic scientific investigation.

Although Burgis emphasizes the first years of making images, she had to compare some of her thinking with the discussion of writer Susan Sonag in On photography (1977). The famous STAG argued that “photography is the suitability of the thing that was filmed” – these images allowed our minds to think about everything we see. This idea resonated with many moments in Flashes of brilliance Where early photo makers were documenting the world, but they turned it into a permanent and possible and possible thing.

Whether the Sysil Shadolt air in London from a balloon or Luis Bhutan for life under the sea, these images are not neutral – they constitute what we believe is true in the world and what we consider worth looking at.