Authors and institutions need to acknowledge problems with published studies when they are found.Credit: Getty

Scientists rightly want to take credit for their discoveries and inventions, and they should. But in addition to receiving credit, scientific authorship also means taking responsibility if problems arise. It is a matter of responsibility and transparency.

Regress is part of science, but misbehavior is not – lessons from the superconductivity lab

Authors need to acknowledge errors in their studies that arise after publication, for example, or if their subsequently published results cannot be verified. Institutions and journals also have clear responsibilities to correct the publication record when needed. As we said previously, this process works best when all parties cooperate.

The process of correcting the scientific record often raises difficult questions, especially when it comes to retractions. For example, what role do institutions and journals play in the retraction process? How should authors allocate and accept responsibility when a study is withdrawn if the data have been manipulated or if there are concerns that it may have been manipulated?

Updated guidelines

The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), a UK-based non-profit organization that advises on standards for scholarly publishing, has considered these questions and updated its guidance for retractions in August 2025 (see go.nature.com/496corh). The new guidelines reiterate previous guidance in highlighting that “authorship requires shared responsibility for the integrity of the research reported.”

They also stress that “if the retraction is due to the actions of some but not all of the authors of the publication, the retraction notice should state that if possible.” But the updated guidance now also states: “This approach will only be appropriate if an institutional investigation concludes that a specific author or authors were responsible for errors or actions. The retraction notice must refer to the institutional investigation.”

nature These updated principles followed a study on lung cancer immunotherapy that the authors have now formally retracted (kw ng et al. nature 616563-573 (2023); Retraction https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-026-10104-7; 2026).

Scholarly communication will benefit from standards of research integrity

The reversal follows an investigation by the authors’ organisation, the Francis Crick Institute in London. The investigation found that in some cases, study data were manipulated, were not reproducible, or were selectively included or excluded (see go.nature.com/4jd1nz6). The authors apologized to the research community and said they were committed to reviewing the study.

The Crick investigation identified one of the authors, named in the institute’s report, as responsible for these analyses. This author’s name was also mentioned in the retraction. We do this in line with COPE guidelines revised following the conclusions of the institutional investigation.

We also did it because credit for science comes with responsibility. Researchers agree to follow a set of behaviors that should live up to the highest standards of integrity. This is what trust in science is built on. If the investigation shows that these standards have fallen, or if this trust has been betrayed, it is right that society holds accountable all those responsible.

Shared responsibility

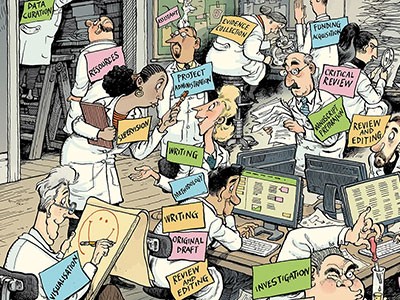

In the current era of team science, researchers have every right to be concerned about the impact on their career and reputation if one or more group members compromises the research integrity of a study.

Crick also deserves credit for acting quickly in his institutional investigations and reporting the results confidently to him natureEditors. It is unfortunate that the lack of sufficient cooperation between institutions and journals leads to parallel and long-term investigations.

Typically, when journals conduct their own investigations, they do so without access to the results of the institutional investigation, if there is one. We have said before that institutional investigations are necessary to assess cases of potential misconduct. Improving communication between institutions and journals is also essential.

A decade’s campaign to recognize authors for their work – and why there’s still more to do

Sometimes, universities may be reluctant to investigate. This reluctance or delay in investigating cases can stem from concerns about damage to the reputation of institutions or their research groups if wrongdoing is uncovered. But the reputational damage caused by inaction can be just as bad, if not worse. It is best to be transparent and admit any mistakes made. We hope that institutions will be encouraged to act where necessary, and to do so quickly, in accordance with COPE guidelines and with journals committed to working with them.

Scientific authorship is a two-sided coin. Credit goes hand-in-hand with responsibility, which is essential for achieving transparency and maintaining trust in science. This responsibility includes admitting when things are not going well.

Withdrawals are part of the scientific process, and we will continue to follow updated COPE guidelines if needed in the future.