Mark Pointing and Matt McGrathBBC News Climate and Science

Kevin Carter/Getty Images

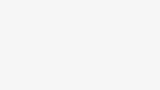

Kevin Carter/Getty ImagesNorth Pacific waters have experienced their warmest summer on record, according to a BBC analysis of a mysterious marine heatwave that has baffled climate scientists.

Sea surface temperatures between July and September were more than 0.25 degrees Celsius higher than the previous record high set in 2022, a significant increase in an area about ten times the size of the Mediterranean.

While climate change is known to increase the likelihood of marine heatwaves, scientists struggle to explain why the North Pacific has been warming for so long.

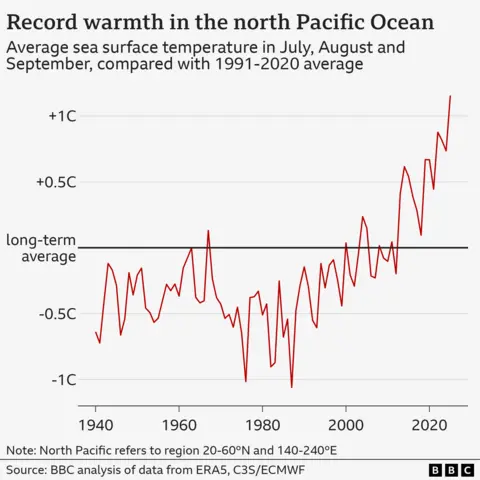

But all this extra heat in the so-called “warm bubble” may be having the opposite effect in the UK, potentially making a cold start to winter more likely, some researchers believe.

“There is definitely something unusual going on in the North Pacific,” said Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at the Berkeley Earth research group in the US.

He added that such a jump in temperatures in an area of this size is “absolutely remarkable.”

The BBC analyzed data from European Copernicus Climate Service Calculates average temperatures between July and September across a large area of the North Pacific Ocean, sometimes known as the “warm bubble.”

The area extends from the east coast of Asia to the west coast of North America, and is the same area used previously Scientific studies.

The figures show that not only has the region warmed rapidly over the past two decades, but that 2025 will be significantly warmer than recent years as well.

The rise in sea temperatures is not surprising. Global warming, caused by human emissions of carbon dioxide and other gases, has tripled the number of extreme heat days in the oceans globally, according to a new report. Research published earlier this year.

But the temperatures were higher than predicted by most climate models — computer simulations that take human carbon emissions into account.

Analyze these models by Berkeley Earth Collection This study indicates that the odds of sea temperatures observed across the North Pacific in August were less than 1% of occurrence in any one year.

Natural weather variability is believed to be part of the reason. For example, this summer saw weaker winds than usual. This means that more of the heat from the summer sun’s rays can stay on the sea surface, rather than mixing with the cold water below.

But this cannot go further in explaining the exceptional circumstances, according to Dr. Hausfather.

“It’s definitely not just natural fluctuation,” he said. “There’s something else going on here too.”

One interesting idea is that a recent change in shipping fuel may be contributing to the overheating. Before 2020, dirty motor oil produced large amounts of sulfur dioxide, a gas harmful to human health.

But this sulfur also formed small, sun-reflecting particles in the atmosphere, known as aerosols, which helped keep high temperatures in check.

So removing this cooling effect in shipping hotspots like the North Pacific could reveal the full impact of human-caused global warming.

“Sulfur appears to be the main candidate behind this warming in the region,” Dr. Hausfather said.

last Research indicates Efforts to reduce air pollution in Chinese cities have played a role in the warming of the Pacific Ocean as well.

This dirty air did something similar to charging, reflecting sunlight away, while cleaning it would have had the unintended consequence of allowing more ocean heating.

Potential impacts on the UK?

The North Pacific marine heatwave has already had consequences for weather on both sides of the Pacific, and will likely bring extremely high summer temperatures in Japan and South Korea and storms in the United States.

“In California, we have had supercharged thunderstorms because warm ocean waters in the Pacific provide heat and moisture,” said Amanda Maycock, professor of climate dynamics at the University of Leeds.

“In particular, there are things we call atmospheric rivers… corpses of air that contain very high amounts of moisture that feed themselves from ocean water,” she added.

“So, if we have warm ocean water, it can bring a lot of moisture to the Earth, which then falls as rain, or it can fall in the winter as snow.”

Reuters

ReutersLong-term weather forecasting is always a challenge, but extreme heat in the North Pacific has the potential to impact the UK and Europe in the coming months too.

This is because of the relationships between weather in different parts of the world known as teleconnections.

Professor Maycock said: “Although the current warm conditions are located in the North Pacific, they could generate wave motions in the atmosphere that could shift our weather towards the North Atlantic and Europe.”

“This could tend to favor high-pressure conditions over the continent, bringing us a greater influence from the Arctic, where we have cooler air,” she added.

“This could be projected onto Europe and bring us colder weather in early winter.”

The colder outcome is by no means certain, as this is a complex area of science. Many other weather patterns also influence UK winters, which typically become milder as the climate changes.

The warmer North Pacific appears to have different effects later in the winter, favoring milder and wetter conditions in some parts of Europe.

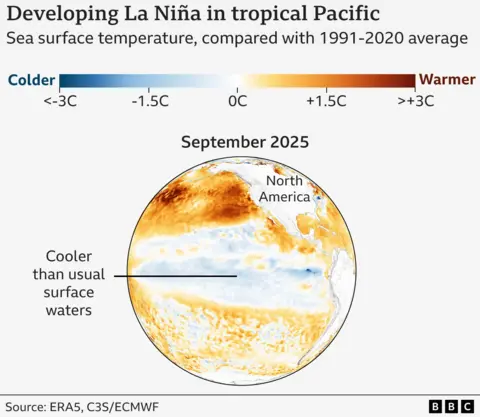

The emergence of the La Niña phenomenon in the tropical Pacific Ocean

Another factor to add to the mix is what’s happening further south in the eastern tropical Pacific.

There, the surface waters are unusually cold – a classic sign of the weather phenomenon known as The girl.

However, La Niña and its warm sister El Niño are normal patterns Research published this week He stressed that global warming could in itself affect the fluctuations between them.

Weak La Niña conditions are expected to persist over the next few months, according to NOAA.

All other things being equal, La Niña generally increases the risk of a cold start to winter in the UK, but also brings a greater chance of a mild end. The Met Office says.

“These two drivers will be working in the tropical North Pacific together this winter,” Professor Maycock said.

“But since La Niña is so weak this year, extreme warmth in the North Pacific may be more important for forecasting next winter.”

Additional reporting by Mosquin Lidar and Libby Rogers